Rank, duty position and unit at time of action:

Captain, Air Corps, Missouri National Guard

War:

None; peacetime noncombat achievement

Place and date of action:

Atlantic Ocean, 20-21 May 1927

Portrayed by:

In the film:

LINDBERGH, CHARLES A.

Rank and organization: Captain, U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve. Place and date: From New York City to Paris, France, 20-21 May 1927. Entered service at: Little Falls, Minn. Born: 4 February 1902, Detroit, Mich. G.O. No.: 5, W.D., 1928; act of Congress 14 December 1927. Citation: For displaying heroic courage and skill as a navigator, at the risk of his life, by his nonstop flight in his airplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, from New York City to Paris, France, 20-21 May 1927, by which Capt. Lindbergh not only achieved the greatest individual triumph of any American citizen but demonstrated that travel across the ocean by aircraft was possible.

[Note: There is some dispute over whether the three men listed in the Peacetime Aviation section of this website, Charles A. Lindbergh, William Mitchell and Charles E. Yeager, were truly recipients of the Medal of Honor, due to the deviations in procedure leading to the awards, and the nonstandard medals awarded to Mitchell and Yeager. Lindbergh and Mitchell are listed on the US Army Center of Military History Medal of Honor Website while Yeager is not. Lindbergh is listed on the Congressional Medal of Honor Society's and the Medal of Honor Historical Society's lists of recipients while Mitchell and Yeager are not. All three men, however, were included in the Gallery of US Army Air Service/US Army Air Corps/US Army Air Force/US Air Force Medal of Honor Recipients at the Air Training Command bases where the two authors attended flight training. We have decided to give each man the benefit of the doubt and treat all three equally; we believed it would have been unfair to include any one of these three individuals while omitting any one other individual, particularly since all three were the subject of movies.]

Lindbergh received the Medal of Honor for completing the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight, 32 straight hours from New York City to Paris in a Ryan craft nicknamed Spirit of St. Louis after the city which sponsored his effort. Contrary to common misconception, it was not the first flight ever across the Atlantic, that feat having been accomplished eight years earlier by a 2-man British bomber crew going a shorter distance, from Newfoundland to Ireland.

Lindbergh's Medal of Honor, and in fact his entire military record, was full of anomalies. The entire project was strictly a privately funded civilian venture, but his achievement, at that point in the history of aeronautical development, was of such magnitude (several others had died attempting it) that he became a national hero, in fact a national obsession, overnight. His eligibility for the Medal of Honor, as a National Guard officer not on active duty, was really stretching it. [Both authors have spent the bulk of their combined total 40 years of military service in the National Guard. Take our word for it!] This was, essentially, a Medal of Honor by public acclamation.

Like the other peacetime Air Force Medal of Honor recipients Billy Mitchell and Chuck Yeager, Lindbergh did prove himself in aerial combat, in this case after the fact, and this is yet another anomaly: by the time the US entered World War II, Lindbergh had resigned his Guard commission, partly due to the controversy over his relationship with the German government and German Air Force chief Hermann Goering in the immediate prewar years. As a civilian employee of United Aircraft Industries, he managed to get an assignment as a technical representative to the 5th Air Force in the Southwest Pacific Theater. In that capacity he began flying P-38 Lightnings with the 49th and 475th Fighter Groups and accompanying them on combat missions. He later in his memoirs mentioned downing at least one Japanese aircraft (and by some word-of-mouth accounts may have become an ace with at least 5 kills against Japanese aircraft), flying as wingman for the two top American aces of the war (and of all time), Majors Richard I. Bong and Thomas B. McGuire (who would both also receive the Medal of Honor). This became common knowledge throughout the Air Force fighter pilot community, but as Lindbergh was strictly a civilian and therefore technically a possible war criminal, and at the very least not protected by the Geneva Convention, the Air Force never officially acknowledged the fact. Lindbergh therefore received what is normally only a military combat decoration for a strictly private civilian peacetime venture, and then later as a civilian fought in combat and never received any official recognition for it. Lindbergh did return to the Air Force reserve components after the war, retiring as a Brigadier General.

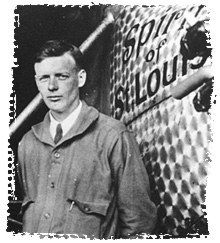

The film is a straightforward account of Lindbergh's preparation for the flight (including the various modifications made on the aircraft to stretch its fuel capacity and range), and the flight itself. This included the fact that he had gone without sleep for two days prior to his takeoff, and a memorable incident in which he fell asleep over the Atlantic, woke up unsure of his position and, finding a fishing boat on the high seas, flew low over it and cut his engine, screaming to its crew "Which way to Ireland?" [This has become known to aviators as the "Fugawee Navigation Method", as in "Where the..."] Casting Jimmy Stewart to play Lindbergh, however, has to fall into the "What the hell were they thinking?" Department. One can assume that the producers thought it a stroke of genius to have Lindbergh portrayed by an actor with so much in common with him; Stewart had left Hollywood to join the Air Force as a pilot before World War II and flew combat missions as a B-24 bomber squadron commander, so like Lindbergh, Jimmy Stewart was a distinguished World War II veteran combat pilot; like Lindbergh, Jimmy Stewart was a high-ranking Air Force reservist; like Lindbergh, Jimmy Stewart eventually retired from the Air Force reserve components as a Brigadier General. Stewart himself, as a young aspiring actor, had vowed to someday play Lindbergh on film. Unfortunately, the film The Spirit of St. Louis was produced to commemorate the 30th anniversary of Lindbergh's flight, and one more thing Lindbergh and Jimmy Stewart had in common was the decade of their birth; at 49 Jimmy Stewart was almost exactly twice as old as Lindbergh was at the time of his flight, and no amount of makeup could compensate for that; the photos on this page should speak for themselves. Lindbergh's youthful exuberance, which explained his drive and his endurance, was sadly never captured in what would have otherwise been a great film.

Lindbergh was also portrayed, more convincingly, by Cliff DeYoung in The Lindbergh Kidnapping Case (1976), although this deals strictly with the tragic kidnapping and murder of his infant son following his attainment of celebrity, and the trial of the accused murderer. The heroic transatlantic flight is depicted only in brief newsreel footage of the real Lindbergh, as part of the opening credits.