Rank, duty position and unit at time of action:

Captain, Test Pilot, US Air Force Test Center

War:

None; peacetime noncombat achievement

Place and date of action:

Muroc Lake, California, 14 October 1947

Portrayed by:

In the film:

Not Available

[Note: There is some dispute over whether the three men listed in the Peacetime Aviation section of this website, Charles A. Lindbergh, William Mitchell and Charles E. Yeager, were truly recipients of the Medal of Honor, due to the deviations in procedure leading to the awards, and the nonstandard medals awarded to Mitchell and Yeager. Lindbergh and Mitchell are listed on the US Army Center of Military History Medal of Honor Website while Yeager is not. Lindbergh is listed on the Congressional Medal of Honor Society's and the Medal of Honor Historical Society's lists of recipients while Mitchell and Yeager are not. All three men, however, were included in the Gallery of US Army Air Service/US Army Air Corps/US Army Air Force/US Air Force Medal of Honor Recipients at the Air Training Command bases where the two authors attended flight training. We have decided to give each man the benefit of the doubt and treat all three equally; we believed it would have been unfair to include any one of these three individuals while omitting any one other individual, particularly since all three were the subject of movies.]

Chuck Yeager was awarded a Medal of Honor by a special act of Congress (making it one of the rare true Congressional Medals of Honor), presented to him by President Ford in 1976, a year after he retired from the Air Force as a Brigadier General and 29 years after the act with which he earned it: being the first man ever recorded to fly faster than sound and breaking what was then known as the "sound barrier". At the time, many aircraft had disintegrated in flight as they approached the speed of sound (or Mach 1) due to the compressibility of the air in front of the craft. Many aeronautical engineers had drawn the conclusion that it was scientifically impossible to break the barrier when Yeager flew a rocket-powered XS-1 aircraft (which he had nicknamed Glamorous Glennis after his wife) launched in midair from a modified B-29 bomber. Approaching Mach 1, the craft withstood the violent buffeting of the compressed air which stiffened the controls, and then the air smoothed out with the controls returning on the other side of Mach 1. At the time, the feat was considered comparable to that of another earlier aviator who in his time had received a peacetime Medal of Honor, Charles A. Lindbergh. Yeager, however, would not get the immediate worldwide recognition and accolades that Lindbergh enjoyed, as the Air Force withheld the news of his feat from the public for over a year and a half due to the security concerns of the Cold War era.

Prior to his feat, Yeager had already proven himself in combat as an ace fighter pilot in World War II, by shooting down five German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters on one mission, and then on another mission in the same week shooting down a Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighter with his piston-engined P-51 Mustang. His final total would be 11 1/2 kills (the half meaning an assisted kill with another pilot). In his autobiography, he states that he considered his combat tour in World War II to be his greatest achievement, surpassing his mission in the XS-1.

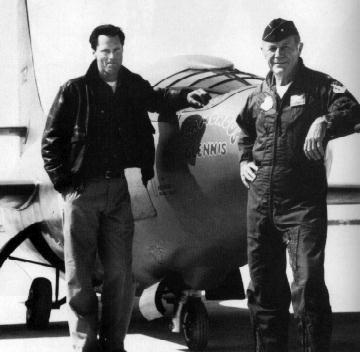

Yeager was a technical advisor on the film and had a cameo appearance as a bartender at Pancho Barnes's Happy Bottom Riding Club, the bar outside Muroc Field that was the test pilots' favored hangout. As in MacArthur, the Medal of Honor action is the beginning rather than the climax of The Right Stuff, with Yeager then being held in awe by the younger test pilots who followed, including those who went on to become America's first astronauts in the Mercury program. In what the authors interpret as a statement about the hype of the space program, the film takes a sequence of the Mercury astronauts and their wives being feasted with Texas-style extravagance at the newly opened Houston Space Center by then-Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson (at a point when fewer than half of them had actually been in space), and intertwines it with a sequence of Yeager quietly taking a specially engined F-104 Starfighter up to the edge of space, experiencing engine failure, bailing out and getting burned by the rocket of his ejection seat, and then calmly walking with his parachute bundled in his arms, his face blackened, away from the flaming wreckage toward the ambulance. The sequence appears reasonably faithful to the actual events as described in the Tom Wolfe book on which the screenplay was based. What is misleading is the impression given that Yeager spent his entire career at Muroc Field (later renamed Edwards AFB) as a test pilot; he did frequently return for tours at Edwards, but he had a well-rounded career as an operational fighter pilot, including flying combat missions in Vietnam as a wing commander after the time span covered in the film.

It is believed that a number of Mustang and P-47 Thunderbolt pilots had flown supersonic in World War II but were unable to verify it in the heat of battle, and that the German Me-163 Komet rocket-powered fighter routinely went supersonic with the Germans not even recognizing the existence of a sound barrier. Still, Yeager has enjoyed recognition for half a century as the first man documented to have broken the sound barrier. In an ironic twist, shortly after he commemorated the 50th anniversary of his feat on October 14, 1997, by replicating the flight in an F-15 Eagle at the age of 73, the Air Force Times reported that a week before Yeager's XS-1 mission, the sound barrier had been broken by North American Aviation test pilot George S. Welch in a prototype F-86 Sabre (the swept-wing jet derivative of the Mustang which would in a few years dominate the skies in the Korean War). This feat was kept secret for even longer than Yeager's, at least originally, because it involved the capabilities of what was soon to become America's front-line fighter, and was apparently forgotten as Yeager's reputation soared. Welch himself very nearly was awarded the Medal of Honor for another action; as an Army Air Force P-40 Kittyhawk pilot, he was one of the few American fighter pilots to get off the ground in Hawaii on the morning of December 7, 1941 and shot down four Japanese planes as they attacked Pearl Harbor. He was nominated for the Medal of Honor but because he had taken off on his own without authorization was instead given the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest award for the Army; he was portrayed by Rick Cooper performing that act of valor in the 1970 film Tora! Tora! Tora!