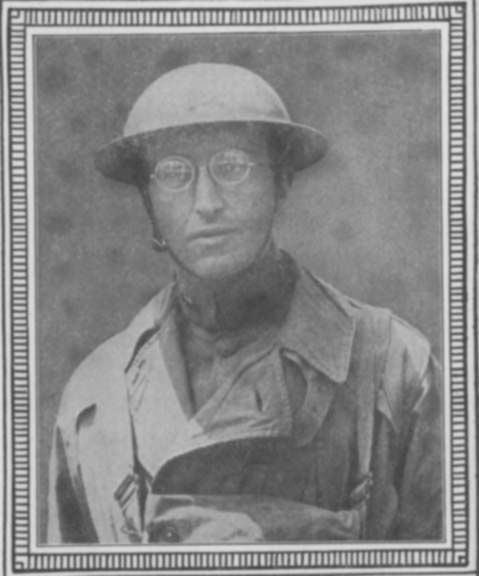

Rank, duty position and unit at time of action:

Major, Commanding Officer, 1st Battalion 308th Infantry, 77th Infantry Division, American Expeditionary Force

Portrayed by:

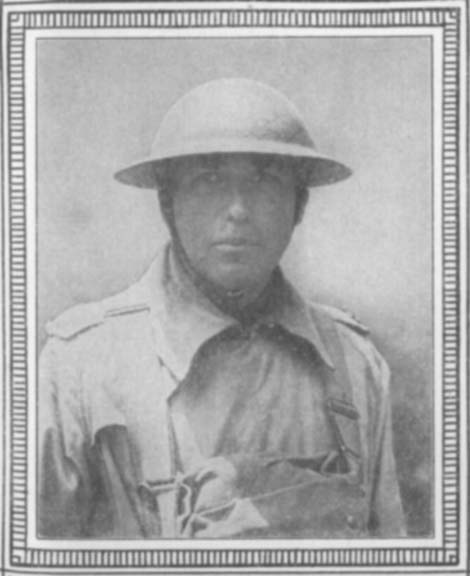

Rank, duty position and unit at time of action:

Captain, Commanding Officer, 2nd Battalion 308th Infantry, 77th Infantry Division, American Expeditionary Force

Portrayed by:

Rank, duty position and unit at time of action:

Captain, Commanding Officer, K Company 307th Infantry, 77th Infantry Division, American Expeditionary Force

Portrayed by:

War:

World War I

Place and date of action:

Argonne Forest, France, 2-7 October 1918

Portrayed in the film:

WHITTLESEY, CHARLES W.

Rank and organization: Major, U.S. Army, 308th Infantry, 77th Division. Place and date: Northeast of Binarville, in the forest of Argonne France, 2-7 October 1918. Entered service at: Pittsfield, Mass. Birth. Florence, Wis. G.O. No.: 118, W.D., 1918. Citation: Although cut off for 5 days from the remainder of his division, Maj. Whittlesey maintained his position, which he had reached under orders received for an advance, and held his command, consisting originally of 46 officers and men of the 308th Infantry and of Company K of the 307th Infantry, together in the face of superior numbers of the enemy during the 5 days. Maj. Whittlesey and his command were thus cut off, and no rations or other supplies reached him, in spite of determined efforts which were made by his division. On the 4th day Maj. Whittlesey received from the enemy a written proposition to surrender, which he treated with contempt, although he was at the time out of rations and had suffered a loss of about 50 percent in killed and wounded of his command and was surrounded by the enemy.

McMURTRY, GEORGE G.

Rank and organization: Captain, U.S. Army, 308th Infantry, 77th Division.Place and date: At Charlevaux, in the forest of Argonne, France, 2-8 October 1918. Entered service at: New York, N.Y. Born: 6 November 1876, Pittsburgh, Pa. G.O. No.: 118, W.D., 1918. Citation: Commanded a battalion which was cut off and surrounded by the enemy and although wounded in the knee by shrapnel on 4 October and suffering great pain, he continued throughout the entire period to encourage his officers and men with a resistless optimism that contributed largely toward preventing panic and disorder among the troops, who were without food, cut off from communication with our lines. On 4 October during a heavy barrage, he personally directed and supervised the moving of the wounded to shelter before himself seeking shelter. On 6 October he was again wounded in the shoulder by a German grenade, but continued personally to organize and direct the defense against the German attack on the position until the attack was defeated. He continued to direct and command his troops, refusing relief, and personally led his men out of the position after assistance arrived before permitting himself to be taken to the hospital on 8 October. During this period the successful defense of the position was due largely to his efforts.

HOLDERMAN, NELSON M.

Rank and organization: Captain, U.S. Army, 307th Infantry, 77th Division. Place and date: Northeast of Binarville, in the forest of Argonne, France, 2-8 October 1918. Entered service at: Santa Ana, Calif. Birth: Trumbell, Nebr. G.O. No.: 11, W.D., 1921. Citation: Capt. Holderman commanded a company of a battalion which was cut off and surrounded by the enemy. He was wounded on 4, 5, and 7 October, but throughout the entire period, suffering great pain and subjected to fire of every character, he continued personally to lead and encourage the officers and men under his command with unflinching courage and with distinguished success. On 6 October, in a wounded condition, he rushed through enemy machinegun and shell fire and carried 2 wounded men to a place of safety.

The actions involving the so-called "Lost Battalion" actually resulted in the awarding of five Medals of Honor. The three recipients covered on this page were appropriately depicted in the film, but the remaining two, Army Air Service aviators Erwin R. Bleckley and Harold E. Goettler, were so misrepresented as to earn this film a second entry under the Blown Opportunities category. And this film, while generally doing justice to the men of "The Lost Battalion", is not without other flaws.

The nickname "The Lost Battalion", coined by the wire service war correspondents at the time, was an oversimplified misnomer of the forces involved, which were actually two battalions (1st and 2nd Battalions of the 308th Infantry Regiment, commanded respectively by Major Charles W. Whittlesey and Captain George G. McMurtry), and elements of two others, K Company of the 3rd Battalion 307th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Captain Nelson M. Holderman, and two companies of the 306th Machine Gun Regiment which were attached to the two battalions of the 308th. The film perpetuates this oversimplification by having Whittlesey in command of a "308th Battalion" with McMurtry as his executive officer. The tactical situation did eventually develop into essentially that type of command relationship over the entire force, since Whittlesey was the senior of the two commanders, but at the start of the operation on 2 October 1918, all three battalions of the 308th Regiment and the remainder of the 77th Division were part of a general corps-sized online offensive through the Argonne Forest. Whittlesey's battalion was the only element to reach its objective of a road junction at the Charlevaux Mill, where they were joined by McMurtry's battalion, while the remainder of the offensive ground to halt and the other Allied forces retired to the trenches of their original Line of Departure. With the primitive communications (carrier pigeons and long telephone lines which were easily cut), the two battalions found themselves in a deep salient which was then cut off and surrounded by the Germans before they realized the situation. Shortly afterward, they were joined by Holderman's company, which had become separated from its parent battalion during the confusion of the stalled advance. The force of approximately 700 men had started off with a single day's worth of rations and no sleeping or foul weather gear.

For the next five days, they fought off repeated attacks by the Germans with much close-in hand-to-hand combat, with a very limited supply of water, stretching their own rations and resorting to eating leaves, grass and whatever food they could find on the German dead. US airplanes attempted to drop food and other supplies to them, but due to poor weather and the uncertainty of their location and that of the surrounding Germans, most of it ended up in German hands. Casualties mounted steadily, straining the already dwindling medical supplies. The situation was then worsened when higher headquarters, acting on information Whittlesey had sent by carrier pigeon, attempted an artillery barrage on the Germans which, due to miscalculations (perhaps on Whittlesey's part), fell short and caused more American casualties than German; Whittlesey used his last carrier pigeon to send a message to tell the artillery to cease fire; it took four hours, with the pigeon reaching its home roost at headquarters badly shot up by German rifle fire, for the message to get through.

The fortunes of the Lost Battalion began to turn on 6 October; Army Air Service pilot1st Lieutenant Harold E. Goettler and his gunner-observer 2nd Lieutenant Erwin R. Bleckley had been among those vainly attempting to drop supplies to the Lost Battalion, frequently returning to base with battle damage to their DH-4 aircraft from German ground fire. On their second sortie of the day, they located and pinpointed the front line traces of both the Lost Battalion and the surrounding Germans, but both men were wounded by ground fire. The DH-4 crash-landed on Allied lines; Goettler was found dead in the cockpit and Bleckley died enroute to the hospital, but his notes and map annotations allowed the Americans to fire more accurate artillery on the Germans and to mount a relief effort. Bleckley and Goettler were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for this action. Unfortunately, in this film, their actions were depicted as being done by a single unnamed pilot with an indeterminate foreign accent in a very brief speaking role, flying a British-made single seat SE-5 fighter with French markings, which earns this film a second separate entry under the Blown Opportunities section.

Shortly before the relief column arrived on 7 October, a private from Whittlesey's battalion, who had been captured by the Germans earlier, returned with a letter from the German commander calling for the surrender of the surrounded Americans, appealing to their sense of humanity and honor to end the suffering. Whittlesey and McMurtry figured correctly that the Germans had to be desperate and on the edge of defeat themselves to have to resort to this, and word of the letter galvanized the Lost Battalion into stiffer resistance. In actuality, Whittlesey ordered his men to take down some white cloth panels that had been put up previously to signal friendly aircraft, to insure that they would not be mistaken by the Germans for surrender flags; in the film, Rick Schroder as Whittlesey throws the Germans' white truce flag and staff back at them javelin-style. [This lesser-known incident would be replayed, almost word for word, on a larger scale a generation later in December 1944, with the 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne, Belgium during the Battle of the Bulge. In that version, the acting commander of the 101st Airborne, Brigadier General Anthony C. McAuliffe, punctuated his refusal of the German demand with a written single-word reply of "Nuts!"]

Of the approximately 700 men of the Lost Battalion, 170 died over the 6 day siege and 360 were carried from Charlevaux Mill on stretchers; fewer than 200 walked out on their own power. But their resistance resulted in a breach of the German lines that eventually facilitated the American breakthrough in the Argonne Forest and led to the end of the war just over a month later. (The three Medal of Honor recipients are among those depicted in the film as walking out with the troops, but there are some inconsistencies between the film and known facts, over the wounds sustained by McMurtry and Holderman; McMurtry's kneecap was reportedly shattered and he probably did not leave on his own two feet.)

The film is seen largely through the eyes of Charles Whittlesey, a Harvard Law School graduate and New York corporate lawyer-turned-soldier. Like Alvin C. York, another American soldier who would earn the Medal of Honor elsewhere in the Argonne Forest a day after the relief of the Lost Battalion, he is depicted as a pacifist who reluctantly takes up arms over a sense of higher duty. Much is made in the film, however, of McMurtry and Holderman being "professional soldiers" (i.e. career Regular Army officers) and Whittlesey being a "civilian"; this is simply not the case. While Phil McKee as McMurtry points out correctly in the film that he was a veteran of Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders and the Battle of San Juan Heights, McMurtry was in actuality among those Ivy League students who answered Roosevelt's call to arms for the 1898 Spanish-American War, leaving his studies at Harvard. Like nearly all the other Rough Riders, he returned to civilian life immediately after the war, returning to Harvard and graduating the next year; he spent the next 18 years as a New York stockbroker and never wore the uniform again until the outbreak of the next war; he was as much an Ivy Leaguer and white-collar New Yorker as was Whittlesey. Holderman was an activated National Guard officer rather than Regular Army. All three of these men were citizen-soldiers.

Perhaps it would have been too much of a down note for the producers of the film to have mentioned (and may also be so for the authors of this website to mention here) that in November 1921, three years after his ordeal in the Argonnne Forest and a few days after serving as an honorary pallbearer at the entombment of the first Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery, Charles Whittlesey committed suicide, evidently suffering from what today is known as post-traumatic stress disorder.

This film could be characterized as essentially a remake of screenwriter James Carabatsos' fictionalized-but-fact-based 1987 Vietnam War epic Hamburger Hill, reset in an earlier war with the real-life historical figures infused into the storyline. Several elements are common to both films, including gritty and sometimes graphic depictions of hand-to-hand combat, higher headquarters decisions that appear nonsensical to the front-line troops, desperate and apparently futile battle over seemingly worthless ground, miscalculations resulting in heavy friendly-fire casualties. This is not necessarily another flaw in the film, but should be seen as a reflection of the fact that, as in other facets of history, things in war do tend to repeat themselves.